Monumental rock carving has been traditionally practiced in India and abroad. In India, rock

carving was a most popular creative mode between the second century BC and the eighth

century AD though its impact continued well beyond this time span. The richest expression of

the art form in India is probably the rock cut temples and sculptures of Ellora, with the Buddhist

series from the sixth to the eighth centuries AD and the Jain series from the eighth to thirteenth

centuries AD. The monasteries, halls of prayer and the monks' living quarters in Ajanta, with

chiselled sculptures, completed between the second century BC and 650 AD are further

examples.

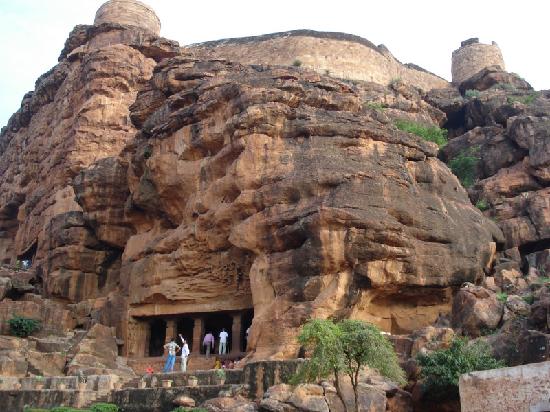

Another example is the great cave of Elephanta, supposed to have been carved between the end

of the eighth and the beginning of the ninth century AD, as are the cave-mandapas of

Mahabalipuram, with the sculptures within and in relief, dated to 625-74 AD. The decline of the

tradition after the eighth century AD has never been explained, but the tradition of smaller

sculptures in stone bear testimony to the tradition.

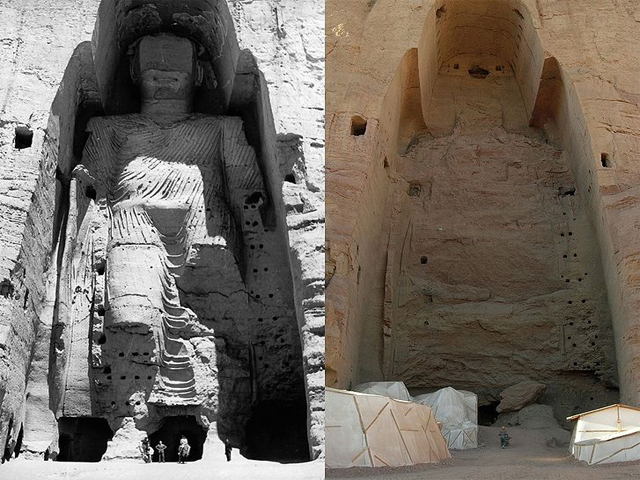

The traces of this mode are also vividly apparent in the international canvas. The Bamiyan

(fourth-fifth centuries BC) in Afghanistan and the Petra (31 BC) monument near

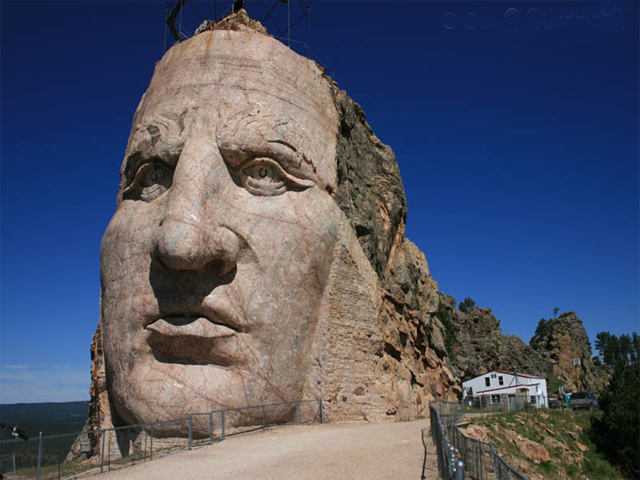

Amman are even older. Monuments like Mount Rushmore (1927-41 AD) and Crazy Horse

(1948-98), both in South Dakota, U.S.A. are modern examples of the same art. Though the technique used in the present

project can be seen as a revival of our ancient rock carving

tradition, the concept is original in its conscious deviation from the religious or political

orientation of all earlier landmarks of the art of rock-carving. The Pakhipahar is conceived

within a more secular and democratic ethos, in its celebration of common humanity and its

aspirations, its yearning for unity, peace, solidarity, friendliness and harmony.